A new law introduced in New York would allow police to take your cell phone on the spot, and analyze it to determine whether you were on the phone, or texting, or reading email, in the moments leading up to the accident. Dubbed the Textalyzer – or Textalizer – the bill’s proponents say that the concept is not much different than a Breathalyzer, which police use on the spot to see whether someone is over the legal blood alcohol limit while behind the wheel.

In fact, much like the breathalizer field sobriety test, New York’s Textalyzer bill starts out by saying that it “[p]rovides for the field testing for use of mobile telephones and portable electronic devices while driving after an accident or collision.”

The bill goes on to say that “The legislature hereby finds that the use of mobile telephones and/or personal electronic devices has drastically increased the prevalence of distracted driving. This destructive behavior endangers the lives of every driver and passenger traveling on New York state roadways. In 2001, this legislature enacted legislation prohibiting the use of mobile telephones while driving, and in 2009 updated the law to include all portable electronic devices. The executive branch initiated a public campaign against cell phone use while driving, and has even established “text stops” along all major highways.

While these efforts have brought much needed attention to the dangers of distracted driving, reports indicate that 67 percent of drivers admit to continued use of their cell phones while driving despite knowledge of the inherent danger to themselves and others on the road. A 10 year trend of declining collisions and casualties was reversed this year as crashes are up 14 percent, and fatalities increased 8 percent, suggesting that the problem has not only gotten worse, but is still greatly misunderstood.” (You can read the full text of the New York breathalyzer bill here.)

Of course, the connection between distracted driving and fatal accidents has long been known. As far back as 2008 (a near-eternity ago in Internet time) a train accident killing 25 was found to be caused by the engineer texting while driving. A train!

The Internet Patrol is completely free, and reader-supported. Your tips via CashApp, Venmo, or Paypal are appreciated! Receipts will come from ISIPP.

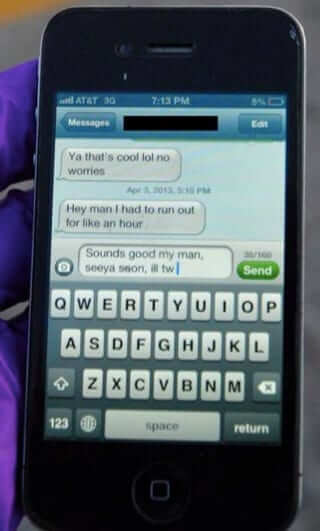

And just a few years ago, in 2013, a heartbroken Colorado family made public their son’s last text – ever – that he was in the process of sending when he fatally crashed his car.

Teenager Alexander Helt’s Last Text Ever

Of course, it’s not just an issue in the United States, it’s happening everywhere (even a member of the British House of Lords was not immune from the siren song of texting while driving, leading to a fatal accident).

Lots of different efforts have been made in an attempt to reduce the incidence of distracted driving. Ford’s vehicle integration of the Life360 app and the Key 2 Safe Driving (K2SD) are two technology-based efforts to inhibit texting while driving.

And nearly all of the states now have a law on the books that in some fashion is intended to discourage distracted driving – usually specifically calling out texting while driving.

Still, the numbers of accidents and deaths resulting from distracted driving continues to climb. (Of course, a study by the Highway Loss Data Institute has concluded that, counter-intuitively, laws banning texting while driving may actually increase the incidence of distracted driving. They suggest that it may be, at least in part, because people are trying to hide their phones on the seat, or in their lap.)

Modern cell phones are not just another technological convenience. With all they contain and all they may

reveal, they hold for many Americans “the privacies of

life.”

But New York’s newest effort takes another tack entirely. Co-sponsored by New York Senator Terrence Murphy and Assemblyman Felix Ortiz, in a joint effort with the organization Distracted Operators Risk Casualties (DORCs), the proposed law relies on technology (the so-called Textalyzer) that is being developed by Cellebrite, a company out of Israel that has been involved in mobile forensics for several years.

One of DORCs founders, Ben Lieberman, lost his 19-year-old son to a distracted driver, but they only know that due to Ben’s own initiative. The driver’s phone was sitting in his car, in a junkyard; it simply had never occurred to local law enforcement to check the driver’s phone. Ben subpoenaed the driver’s phone records, and that’s how they learned that he had been texting while he was driving, leading up to the crash.

Says Lieberman, in a statement, “I have often heard there is no such thing as a breathalyzer for distracted driving – so we created one.”

Lieberman adds, “Respecting drivers’ personal privacy, however, is also important, and we are taking meticulous steps to not violate those rights.”

However, those steps may not be enough. While the bill’s authors, and Cellerite, assure that data will not be able to be read (so the police would not have access to the content of messages, only to records indicating the timing of them), in 2014 the Supreme Court held in the case of Riley v. California that “Modern cell phones are not just another technological convenience. With all they contain and all they may reveal, they hold for many Americans “the privacies of life.” The fact that technology now allows an individual to carry such information in his hand does not make the information any less worthy of the protection for which the Founders fought. Our answer to the question of what police must do before searching a cell phone seized incident to an arrest is accordingly simple – get a warrant.”

Still, the bill’s sponsors are moving it forward, based in part on a theory of implied consent, and if it passes, and isn’t struck down, you can be sure it will be exported to other states. In fact, Cellebrite is already looking forward to it. Says Cellebrite’s CEO, Jim Grady, “We look forward to supporting DORCs and law enforcement – both in New York and nationally – to curb distracted driving.”

The Internet Patrol is completely free, and reader-supported. Your tips via CashApp, Venmo, or Paypal are appreciated! Receipts will come from ISIPP.