A Federal court has ruled that Microsoft is within its rights to refuse to comply with a U.S. warrant that demanded the production of email stored on a Microsoft server located in Ireland. The decision in the lawsuit, involving a warrant issued by the government under the Stored Communications Act (SCA), was handed down by a Federal Court of Appeals in the United States, meaning that unless the Feds want to take it to the Supreme Court, it is now the law of the land.

In the original case, which started at the end of 2013, a Federal District judge issued a warrant on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) requiring Microsoft to cough up the email of a certain account hosted with Microsoft. However, that particular account was hosted on a server located in Ireland.

Microsoft refused to comply with the warrant, issued under the Stored Communications Act (SCA). Microsoft’s position, and reasoning, was that if the government wanted access to data stored in Ireland, then they should direct their request (warrant) to the appropriate Irish authorities, in Ireland, under the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) that was signed between the United States and Ireland in 2001. The Feds’ position was that because Microsoft is itself a U.S. company, they should not have to go through the U.S.-Ireland MLAT.

The United States has MLATs with dozens of countries, far too numerous to detail here (however you can view a full list of countries with which the U.S. has MLATs here). The MLAT between the United States and Ireland, “[Page no longer available – we have linked to the archive.org version instead]“, was signed on January 18, 2001, as a result of “The Government of the United States of America and the Government of Ireland, desiring to improve the effectiveness of the law enforcement authorities of both countries in the investigation, prosecution, and prevention of crime through

cooperation and mutual legal assistance in criminal matters.”

The MLAT between the United States and Ireland includes, among other things, that:

The Internet Patrol is completely free, and reader-supported. Your tips via CashApp, Venmo, or Paypal are appreciated! Receipts will come from ISIPP.

1. The Parties shall provide mutual assistance, in accordance with the provisions of this Treaty, in connection with the investigation, prosecution, and prevention of offenses, and in proceedings related to criminal matters.

2. Assistance shall include:

(a) taking the testimony or statements of persons;

(b) providing documents, records, and articles of evidence;

(c) locating or identifying persons;

(d) serving documents;

(e) transferring persons in custody for testimony or other purposes;

(f) executing requests for searches and seizures;

(g) identifying, tracing, freezing, seizing, and forfeiting the proceeds and instrumentalities of crime and assistance in related proceedings;

(h) such other assistance as may be agreed between Central Authorities.

3. Except when required by the laws of the Requested Party, assistance shall be provided without regard to whether the conduct that is the subject of the investigation, prosecution, or proceeding in the territory of the Requesting Party would constitute an offense under the laws of the Requested Party.

credit: mlat.info

Because this month’s decision comes from a Federal Court of Appeals, the only place that the DOJ has to go to appeal this is the United States Supreme Court.

(Quick civics lesson: There are 94 Federal District Courts, which are the trial courts in the Federal system. Decisions of the Federal District Courts can be appealed to United States Courts of Appeals, also known as Circuit Courts. Thus, when you hear, for example, that the “9th Circuit” has handed down a decision, that means that it is an appellate level decision. The Courts of Appeals (“Circuit Courts”) are one step below the United States Supreme Court (USSC). The USSC takes appeals from the US Courts of Appeals (Circuit Courts). So, because this decision was handed down by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, the only place for the DOJ to take it now is the Supreme Court. You can read more about our Federal court structure here.)

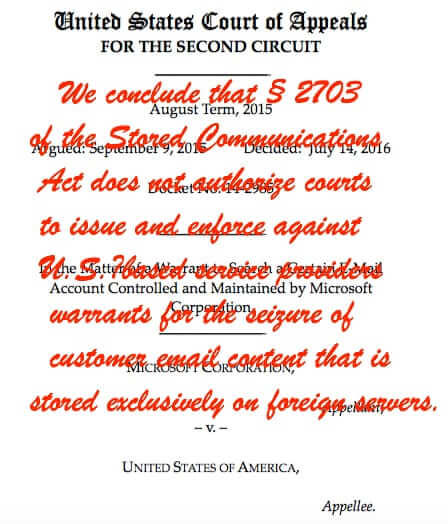

We conclude that § 2703 of the Stored Communications Act does not authorize courts to issue and enforce against U.S.-based service providers warrants for the seizure of customer email content that is stored exclusively on foreign servers.

Explains Justice Susan Carney, in the primary opinion, “The magistrate judge noted the ease with which a wrongdoer can mislead a service provider that has overseas storage facilities into storing content outside the United States. He further noted that the current process for obtaining foreign-stored data is cumbersome. That process is governed by a series of Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (“MLATs”) between the United States and other countries, which allow signatory states to request one another’s assistance with ongoing criminal investigations, including issuance and execution of search warrants. These practical considerations cannot, however, overcome the powerful clues in the text of the statute, its other aspects, legislative history, and use of the term of art “warrant,” all of which lead us to conclude that an SCA warrant may reach only data stored within United States boundaries.”

Justice Carney goes on to say:

We conclude that Congress did not intend the SCA’s warrant provisions to apply extraterritorially. The focus of those provisions is protection of a user’s privacy interests. Accordingly, the SCA does not authorize a U.S. court to issue and enforce an SCA warrant against a United States-based service provider for the contents of a customer’s electronic communications stored on servers located outside the United States. The SCA warrant in this case may not lawfully be used to compel Microsoft to produce to the government the contents of a customer’s email account stored exclusively in Ireland. Because Microsoft has otherwise complied with the Warrant, it has no remaining lawful obligation to produce materials to the government. (Emphasis added.)

You can read the full Microsoft v. United States re: stored server in Ireland here.

It should be noted that this decision does not mean that the Feds can never get at your data if it is stored overseas. It means that they have to invoke the MLAT between the U.S. and that country, or to otherwise go through the host country’s channels.

The Internet Patrol is completely free, and reader-supported. Your tips via CashApp, Venmo, or Paypal are appreciated! Receipts will come from ISIPP.